Ukoo Flani Mau Mau –The Disappearing Acts of a Hip Hop Dynasty

The hip hop group bequeathed Kenya a unique and identifiable hip hop soundscape, and their oeuvre remains the only most studied by urban music archaeologists, but what happened?

The hip hop group bequeathed Kenya a unique and identifiable hip hop soundscape, and their oeuvre remains the only most studied by urban music archaeologists, but what happened?

They were childhood friends, ate from the same plate, and pioneered a new genre, Swahili and Sheng rap, a style that ripped Kenya’s hip hop landscape with an unending laser beam of lyricism and linguistic inventiveness, served, sometimes with a slew of menace and quirky jokiness, sometimes with Mafioso-like braggadocio, and sometimes with the wisdom of self-reflection, but always reporting from the battlefront about the pot holes in our culture – colonialism, post-independence betrayals, endemic corruption, police brutality, street life, and the painful sting of poverty in the ghetto.

It was a new form of musical protest, authentic, germinal, gritty and startling in its boldness.

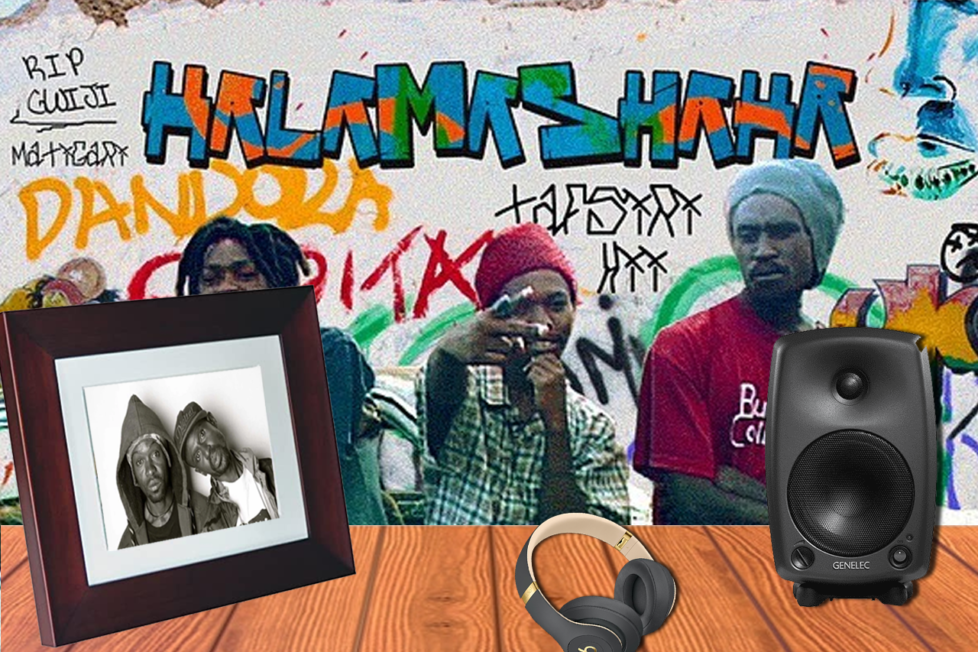

Kalamashaka was founded in 1995 by three musicians – Kamau Ngigi or just Kama, Johnny Vigeti and Robert aka Oteraw. In 1997, Kalamashaka released Tafsiri Hii, a veritable classic, produced by one of Kenya’s long-standing super producers, Tedd Josiah. It became a blueprint, paved the way for the mainstreaming of Swahili hip-hop in East Africa, and introduced music lovers to hardcore rap mashed with socio-political consciousness.

The group’s first album, Ni Wakati, was so successful that one of its singles, Fanya Mambo, produced by Ken Ring in Sweden, catapulted Kalamashaka to international fame, rising to the top spot in South Africa’s Channel O – an arbiter of hip hop success at the time.

Kalamashaka burst out of the seams of music and became a mainstream phenomenon. It gave Dandora youth a cool alternative to the street life and kept young people from violent crime. Juliani says that ‘being a member of Mau Mau Camp was a privilege. It was the royal family of Kenyan Hip Hop’. To join, apprentices like Juliani ‘went to the extent of washing Johnny K-Shaka’s boots just to be close to him and feed on the crumbs of his creativity. Be close just in case he decided to give away a clue on how he does it. If he smoked, we’d smoke. If he stayed up all night, he wouldn’t sleep. If he listened to someone, we would study them even more.’

Dandora estate, established in 1970s to offer a higher standard of housing with partial funding from World bank, now a slum, became the capital of Kenyan hip hop. To help nurture talent from Dandora to Mombasa to Arusha, K-Shaka morphed into a super group: Ukoo Flani Mau Mau.

It was a diverse coterie of artists, as many as 25 members, collectively releasing more than 800 musical tracks, 42 music videos – some with extensive footage from audiovisual historical archives.

Loss of Strategic Direction

The group grew too big too fast making it difficult to steer. They fell out with the high-handedness of Nynke Nauta, a Holland music promoter, who helped record and promote the album, Kilio cha Haki, in 2004.

Nynke was quoted saying that “they would be late for recordings, come drunk, sniffing glue and smoking. They even made advances at me! They called me a white supremacist and other bad names. One of the K-Shaka guys physically assaulted me.”

Just like RZA maintained a high-handedness, during the Wu Tang’s formative years, putting a method to the mad creativity of the group, struggling to mould, say, Ol’Dirty Bastard’s hyper, off-kilter rhymes, and snake charmer melody, into a style, Ukoo Flani owed its stylistic inventiveness to its benevolent producers.

Without support from producers like Tedd Josiah, Ken Ring and Ambrose Akwabi, and promoters like Nynke Nauta and Ciro Githunguri – Ukoo’s official graphic designer, art curator, artist manager, Kenya’s first female DJ and photographer – perhaps the group would never have achieved what it did.

A strategic vision and intent helps in modelling a style – the soundscape through which the geyser of content can be channelled and maintains a group’s creative camaraderie.

With no veritable producer to refine the endogenetic ore deposits of talent into musical gold, andno strong strategic intent to steer Ukoo Flani ship away from the 100-feet high waves threatening to crash the vessel, realign the group with the changes in the music industry, and anticipate the dynamism of tastes and preferences among a new generation of listeners, the ship drove straight into tempestuous storm and has never recovered.

This is the story of many grand hip hop groups that have declined in prominence or collapsed, to give way for the single artist, the single commercial brand, whose identity and appeal is easier to manage by teams of super marketers.

In 2012, Michael Cohen, wrote about the Decline of Hip Hop Groups in the US, citing label politics and the pursuit of individual fame as the main reason behind the collapses. The same can hardly be said about Ukoo Flani, which continues to exhibit strange appearing and disappearing acts, and whose boundaries, membership, and collaborative projects are increasingly becoming difficult to track.

Lukewarm Comebacks

It is common for artists to try to re-enact long lost fame, but what is often forgotten is that artistic success is a product of time.

Time is the creator of the cultural and aesthetic response to art and explains the lukewarm response to Kalamashaka’s attempt to captivate the listenership of today.

In 2008, the group released an album, Mwisho wa Mwanzo, which despite showcasing solid lyricism failed to ripple. Kama released an album, Kama, in 2009, produced by Ambrose Akwabi, and Johnny Vigeti, released Mr. Vigeti, produced by Ken Ring in 2015.

Mr Vigeti is a lodestar, arguably the best-produced hip hop album in Kenya today. It a remarkable experience, aesthetically and emotionally rewarding, but just like Dave Heaton, noted in 1991, when reviewing The Low End Theory, the second album, from the legendary group, A Tribe Called Quest, “anything really worth writing about is nearly indescribable; that’s the conundrum of writing about music”, and probably no words can capture the enthusiasm that followed the rebirth of Johnny Vigeti, especially after years of unending negative press on the degenerating lives of Kalamashaka.

The album features Jamaican international stars: Gramps Morgan and Lutan Fyah, as well as Kenya’s dancehall throb, Wyre, and hip hop head, Abbas. The lead track, Mr Vigeti, details the valleys and thorns the artist has walked. The introspective track, Mama, featuring the Congolese songstress Alicious Theluji, of the delectable Posa ya Bolingo, is a tearful tribute to mothers. Alicios fuses rumba, zouk, and Afro-pop melodies. However, the 12-track album has received minimal play, despite Vigeti distributing 25,000 copies of the album across the country.

In an industry whose music vision has been subsumed by subgenres, Kapuka and Genge, and many other not-so-clearly-defined categories, a comeback needs much more. It has to be more than a cautionary reunion to satiate the thirst and cuddle the nostalgia of aging fans.

A comeback must be a complete transformation, or at least project a futuristic imagination that has the ability to challenge current norms or, at best, push the prevailing trends to new realms. It is then that an artist can gain a new legion of fans and retain older ones, even if a sizeable number of older fans remain stuck in the old era and are unable to appreciate the new artist. An artist of the time is an innovator, one who constantly re-invents themselves, whose aesthetics constantly disrupt trends.

Inheritors of the Dynasty

Rising up the imaginary rank of ‘who is King’ in Kenya’s jungles is no easy task. But the hardest, the iron-wrought, young men, most times from sprawling slums – these minefields of talent, wade through bee-infested rap battles, with a truckload of attitude and skills, hope, and a folded note for bus-fare back home hidden in the innermost pockets, and a truckload of attitude and skills. Juliani, an off-shoot of Ukoo Flani, an exemplar and a most exportable voice, who just released the Mtaa Mentality (2016) album, can attest to this.

Yet Ukoo Flani’s historicising of Dandora, along the trope of the projects, with songs like Dandora L.O.V.E, just like Nas did for Queen’s Bridge or Wu Tang did with the mythical Staten Island, has influenced groups like Y.G.B (Young, Gifted, Black), fronted by Octopizzo, which uses Kibera slums as its canvas, or even individual artists like Khaligraph Jones – a rapid fire with an enviable display of versatility, adaptability, and rhythmic experimentalism – who uses Kayole to reaffirm his street cred.

Other younger artists, still making their bones, like Trabolee and Romi Swahili, are more drawn to poetic lyricism and historical memory, and are in a bruising contest for Kenyan ears with Genge and Kapuka scions, make-believe rhymesters, with the attitude of fake it till you make it.

Today, Ukoo Flani is like a demobilized nationalist militia, bored and frantic, but with no war to fight. The days when the Mic was a battle for personal freedom are fading and they are unable to re-invent themselves. Still, the legendary storytelling of Kitu Sewer in Pesa, Pombe, Siasa na Wanawake or Magazeti, Maradio Na T.V, the grit of Mangirima or DC Na Sisi, the lyrical deftness of Mizani or Kuwaharibia, the deeply introspective tendons of Mama, or the eclectic urbanity of Moi Avenue, testify that other dogs are yet to earn the license to urinate on Ukoo Flani’s iron gate.

***

This article was first published by This Is Africa on November 1, 2016.