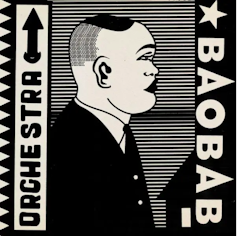

Rudy Gomis: A Masterful Collaborator Who Kept the Diversity of Senegalese Music Alive

The world has lost one of the great pioneers of the post-independence movement of modern popular music in Senegal.

The world has lost one of the great pioneers of the post-independence movement of modern popular music in Senegal.

Lucy Durán, SOAS, University of London

The world has lost one of the great pioneers of the post-independence movement of modern popular music in Senegal. After a long illness, Rudolphe “Rudy” Clément Gomis – co-founder of the famous Orchestra Baobab, bandleader, composer, singer and percussionist – passed away on 27 April 2022 aged 75 in his native city, Ziguinchor, the capital of the Casamance region in southern Senegal.

He had not been able to perform with the dance band for some time, but his hypnotic ballads such as Coumba and Utrus Horas – with their powerful lyrics, luxurious melodies and deep groove – remain among Baobab’s most iconic songs, still entrancing after nearly half a century.

As a singer and songwriter, Gomis had a genius for “fusing humour with melancholy,” as veteran singer Amadou Sarr said to me in a note from his old friend’s funeral. This was not just in Gomis’ philosophical and metaphorical lyrics, but also in his talent for soulful melodies. On songs like Coumba, his slightly rough, expressive voice moves beautifully between pathos and optimism.

Gomis was a key player in creating the distinctive style of Orchestra Baobab, a band made up of outstanding musicians from different parts of Senegal as well as from Mali and Togo. Much of their success was due to his leadership qualities and collaborative spirit. Fifty years on, Orchestra Baobab continues to keep alive the diversity of music in Senegal and travel the world with it, thanks in no small part to Gomis.

Gomis was the last surviving of the band’s founders. He formed Orchestra Baobab in 1970 in Dakar together with two other exceptional musicians, the singer Balla Sidibé also from Casamance, and Berthèlemy Atisso, the guitarist from Togo. They had already been working together in a small band called Standard, incubating a collaborative, cosmopolitan and varied style.

During the 1970s in Senegal many of the local bands did mainly cover versions of Cuban hits from the 1950s, singing in pseudo-Spanish. But with Baobab, the references to Cuban music were subtly reworked within other musical idioms into new composition, and this delicious mixture was part of their charm.

Of all the bands that animated Dakar nightlife in the 1970s, they were the most professional both live and in the studio, always perfectly in tune with masterful, sophisticated arrangements and deep groove.

Senegal gained independence in 1960. Playing at the chic Baobab nightclub in central Dakar for the political establishment, the band enjoyed great success throughout the 1970s, releasing iconic albums like On Verra Ça (We’ll See). “Yes, we were very popular, but this didn’t translate into making a good living,” commented Gomis) in an extensive interview with me back in 2001, housed in the British Library Sound Archive.

At this time we had a Catholic president, (Léopold Sédar) Senghor, who said you can play French and Cuban styles … But then, after the early 1980s, people in Senegal lost interest in the Baobab sound. Instead they just wanted to hear Wolof music.

The Wolof are the majority ethnic group and language in Dakar and in the north of Senegal. In 1980, the new president Abdou Diouf, a Muslim of Wolof ethnicity, ushered in a different social and cultural dynamic.

Despite having many superb songs in Wolof in their repertoire, like Mohamadou Bamba sung by Wolof singer Thione Seck, Baobab were uncomfortable going full force into the Wolof-derived mbalax, the musical style later popularised by Youssou N’Dour.

The band eventually broke up in 1985. But they would be reunited in 2001 – and went international.

Gomis’ background is a crucial factor in the unique style and appeal of Orchestra Baobab. He championed a multi-ethnic sound, a natural response to the environment in which he was raised. Senegal is divided into two regions by the Gambia river. To the south, the lush Casamance, where Gomis was from, encompasses a multitude of languages, religions and musical traditions not found elsewhere in the country and under-represented on a national level. https://www.youtube.com/embed/08S9UYUXZYA?wmode=transparent&start=0

Gomis explained that his Guinea Bissau heritage is evident from his surname. His grandfather, of Manjak ethnicity, was born in Guinea Bissau (then Portuguese Guinea). The Manjak were largely Christianised and given Portuguese surnames, such as Gomes which became creolised into Gomis. Their musical traditions are part of a much wider culture shared across the Black Atlantic, and their main language is Kriolu, a mix of local languages with elements of Portuguese. This was the language that Gomis spoke at home, and many of his songs are in Kriolu, like Utrus Horas and Cabral.

His first taste of playing music was asiko:

At Christmas, new year and at marriages, my family would play the asiko drums; the whole neighbourhood would do the singing around us.

Also known as gumbe, asiko is a type of festive drumming that was brought to the coast of West Africa from Jamaica in the 1800s by resettled Maroons. Rudy did not know about the origins of asiko, but it was a bridge onto other Caribbean styles like reggae and Cuban son, and across diverse African musics. Asiko, he later said, “connects me with the whole coast of Africa, all the way down to Angola”.

Rudy Gomis’ father was a strict ship captain. Rudy worked hard at school but his passion was music:

I would go to nightclubs in Ziguinchor to see different bands and I thought, I could do better than that singer, why am I paying money to hear him? So I asked my father, if I get high marks, will you give me what I ask for? What I wanted was a guitar. He agreed.

He practised every day, listening to diverse recordings. His favourites were the music of Cuban orchestra Orquesta Aragón, traditional styles from Casamance and Guinea Bissau, and the voice of Gambian griot singer Laba Sosseh, popular at the time. Traces of all these sounds and influences can be found in Baobab’s music. Part of what makes their music so special is that there is something in it for everyone.

In Senegal at the time people who were not born into hereditary lineages of artisans – the so-called “griots” – were not supposed to play music.

My father said, ‘No, you’re not a griot … You give up guitar and carry on with your studies, or you leave.’ I chose to leave. But even before I could do so, my father threw my suitcase out of the house.

After Orchestra Baobab broke up, Gomis, a trained language teacher, founded his own language school (named Baobab Centre) in Dakar, where he taught the many languages spoken in southern Senegal and Guinea Bissau. The band members stayed in touch, and occasionally played together. https://www.youtube.com/embed/B2S_l_WFriU?wmode=transparent&start=0

Legendary producer Nick Gold, Youssou N’Dour and others urged Orchestra Baobab to get back together. Gold had re-released their 1982 album Pirates’ Choice through World Circuit Records and it reached international audiences, where their recordings began to attract a cult following. Orchestra Baobab got back together in 2001, launching their new international career.

Under leadership from Gomis they revived their old collaborative spirit, this time recording under better conditions and with some superb guests. A series of successful new albums were released, bringing new and old songs to audiences around the world.

In 2020 Gomis could celebrate 50 years since Baobab was founded. Back in 2001, in the flush of excitement over their reunion, he told me:

I have unpublished songs in my pocket. I’m a composer. It’s my job in this band … We want to make great music for all time.

Orchestra Baobab will carry out these wishes, no doubt.

Lucy Durán, Professor of music, SOAS, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.