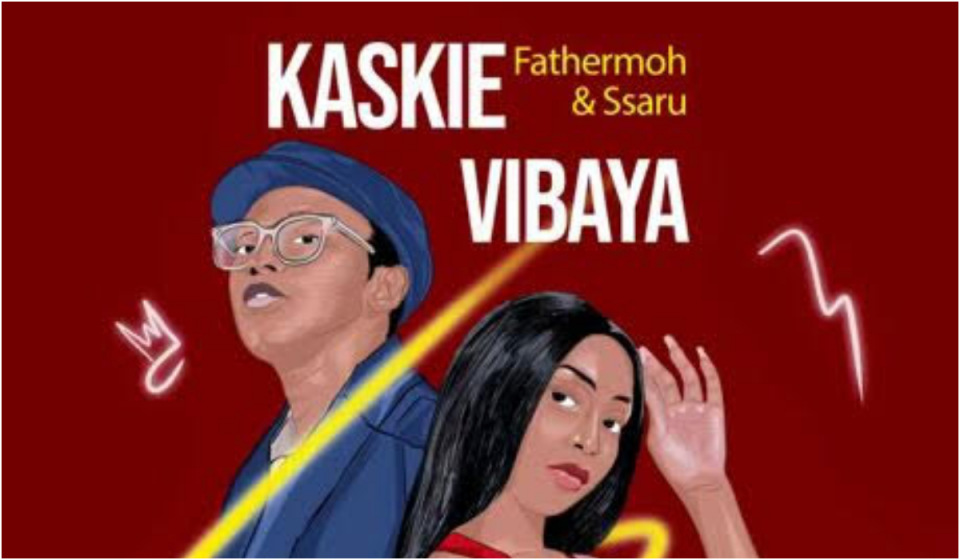

Kaskie Vibaya and the Semiotics of Gengetone

“Kaskie vibaya huko kwenu!” A retort. Witty. Acidic. It stings. Go cry at your home. Go be in your feelings at your home. Go be in your emotions at your momma’s house. Go feel bad somewhere else. If you are not familiar with the phrase, you might be the only Kenyan who isn’t.

This is a great analyis