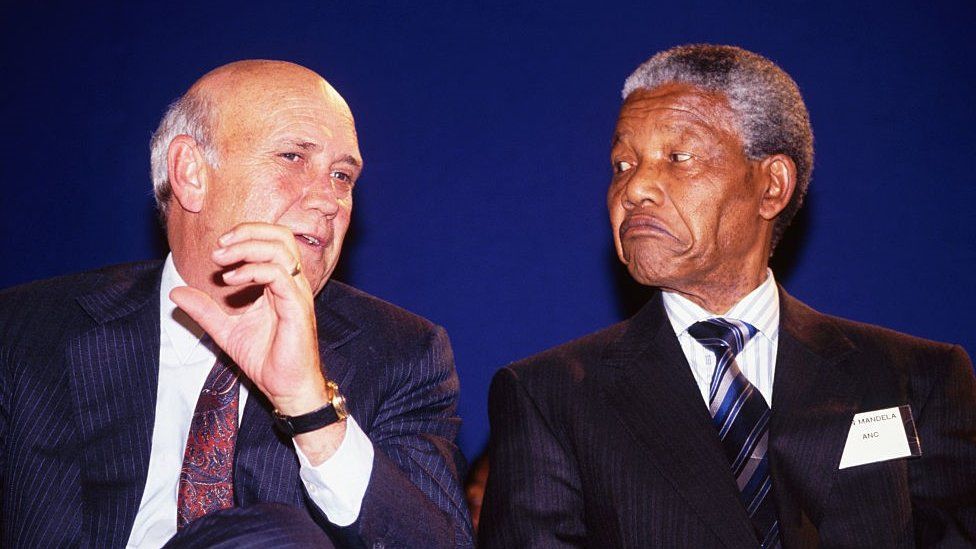

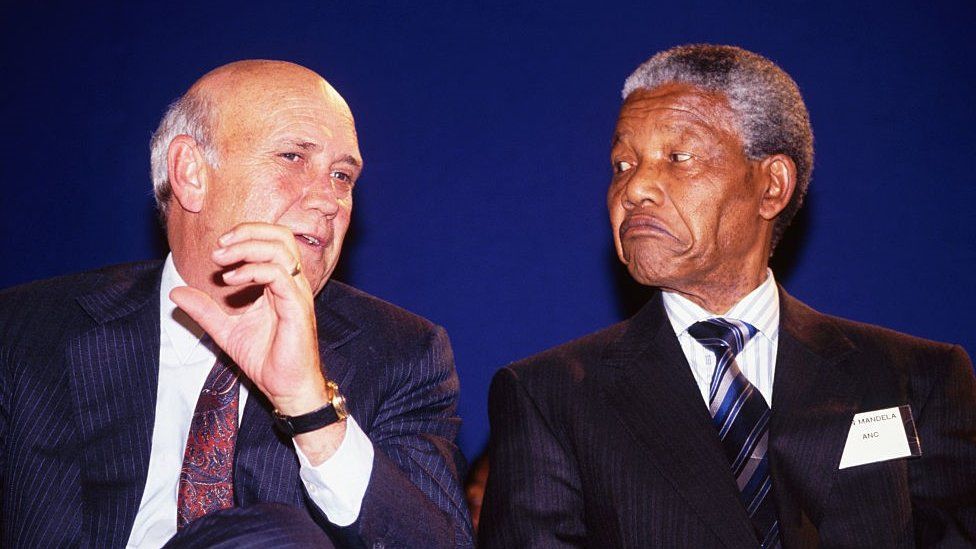

South Africa’s Last Apartheid President Is Dead. How Shall We Mourn FW De Klerk?

De Klerk, despite taking the road not a taken in the sunset days of the 1980s, was a man accepting reality but with blood on his hands.

De Klerk, despite taking the road not a taken in the sunset days of the 1980s, was a man accepting reality but with blood on his hands.

What if we were De Klerk? Would we have acted any better?

The death of FW De Klerk is definitely going to polarise South African public consciousness and the world at large. In the age of identity politics, people are going to remember De Klerk through some interesting lenses, but they will converge on race and ethnicity. Forgive me if I get carried away, too.

Let me tell you my story.

I first came to terms with the traumatising legacy of Apartheid when I landed at the Oliver Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg one chilly afternoon in the winter of 2018. To be precise, I arrived on Labour Day (in South Africa it is called Workers Day) after taking a long bus ride (it must have been a 12-hour ride) to Grahamstown in Eastern Cape for graduate studies at Rhodes University.

Now, Eastern Cape province is home to Nelson Mandela, Steve Biko, Govan Mbeki (Thabo Mbeki’s father) and singer Zahara, among other prominent South Africans. And the province is also predominantly home to the Xhosas (the ethnic group that speaks with a click sound).

Back to De Klerk.

I agree with those who say that he should be lauded for his heroic act in releasing Mandela from prison and making concessions to the African National Congress. And literally saving the country from going to the dogs.

The 1980s were extremely trying times for South Africa. The intransigence of the National Party, De Klerk’s party, nearly pushed the country to a civil war. The situation was so dire, that Oliver Tambo, according to Mandela’s authorized biographer, reportedly ordered the umkhonto we sizwe (ANC armed wing) cadres to start killing innocent white civilians so that the Apartheid upper echelons could see some sense. Of course, they dithered, and this set off a toxic chain of violence and revenge killings that had come to define South African life; a traumatic legacy that lingers on to date.

In other words, De Klerk, despite taking the road not a taken in the sunset days of the 1980s, was a man accepting reality but with blood on his hands.

In my everyday interactions with South Africans in Grahamstown, Port Elizabeth, Pretoria and Johannesburg, there was always this nagging feeling I felt among mostly blacks that the past was an unfinished business. Not in that introspective or even philosophical sense whereby the past is a mirror to help us make sense of the present or even imagine what the future may look like, but the past as a deep wound. It refuses to heal, not of its own accord, but because the pain of that first stab remains complicated, and is entangled in knots of economic neglect and a series of betrayals by the first democratically elected government, ANC.

There were lonely moments during my graduate school years when I used to wonder whether South Africa will ever break out of the dark shadow of De Klerk’s Apartheid nightmare that wasted dozens of lives and planted the seeds of deep-seated hate and distrust between black and whites that has refused to end.

Of course, I cannot absolve ordinary South Africans of the mess that the country has turned out to be. Indeed, they have been participants and actors in the deterioration of political relations between races and clinging on to guilt-tripping tactics at times, and electing leaders with questionable characters, and sometimes scapegoating others at times, not just whites, but also their African brothers and sisters. I repeat, ordinary South Africans cannot escape the blame, if we are to frame the South Africa crisis, as a matter of blame game. Though it is always closer to that.

But ordinary South Africans, in the words of Mbeki, are also my people. Also, De Klerk is one of my people. Yes, he was part of a monstrous regime that remains a stain on the conscience of humanity, and that we are called upon to condemn. But we are still obligated to ask ourselves that if we were in his shoes, would we have acted any better?

May the old man’s soul rest.